Pain and Memory

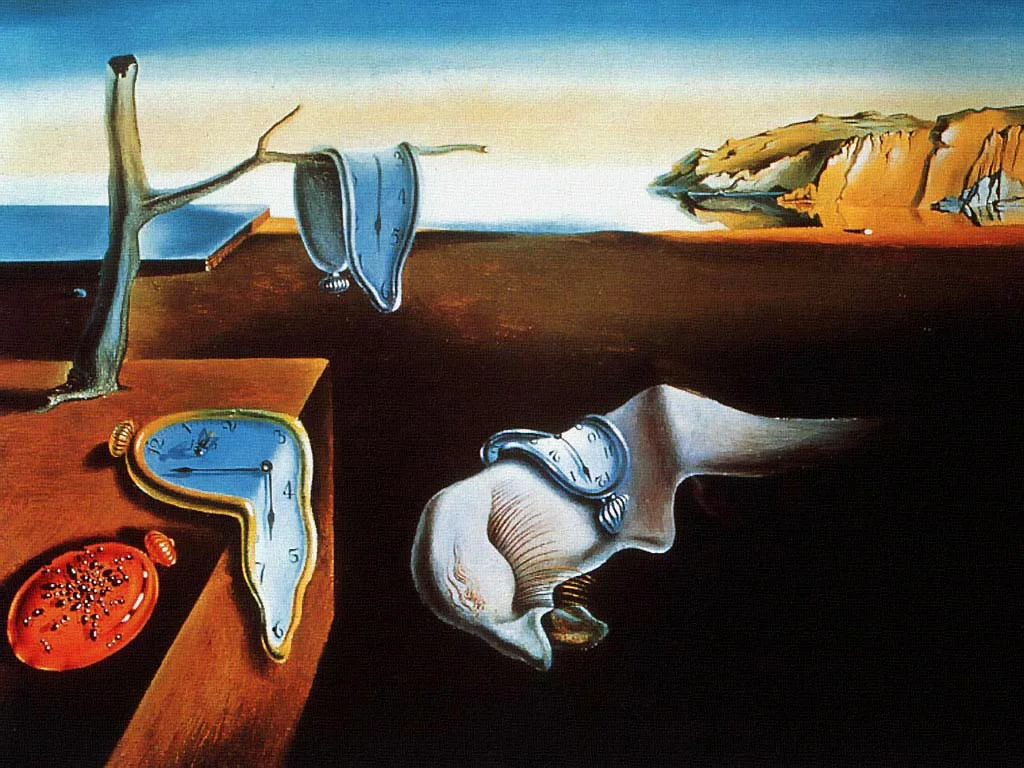

Louis Gifford said that learning about the biology of memory was very informative to his understanding of chronic pain.For example, he thought certain pains were like advertising jingles that get stuck in your head- they're annoying, don't serve any purpose, and are hard to get rid of.

Here are some other interesting connections between pain and memory.

Phantom limb memories

People with phantom limb pain have vivid perceptions that a missing limb is present and painful. Although there are no sensory signals coming from the missing limb, the parts of the spinal cord and brain that process these signals remain, and they can get activated by mistake. When this occurs, they create perceptions about the limb that feel uncannily real.

Ronald Melzack showed that these perceptions are congruent with memories of how the limb felt prior to amputation. For example, phantom limb pain is less severe in people who were not in pain immediately prior to amputation.

Blocking pain memories with drugs

Clifford Woolf performed research showing that if surgery patients receive painkillers before the surgery, they experience less pain after the surgery. Why would that be, if the drugs eventually wear off and do nothing to prevent the tissue damage resulting from the surgery?

His explanation is that post-surgical pain is caused in part by “pain memories” created during surgery, and that the formation of these memories can be blocked by “preemptive analgesia.” According to Woolf:

the post-operative pain is a manifestation of switching on the memory of the pain that occurred during the surgery. … As we search for the molecular basis of pain, we keep uncovering associations between pain and memory. Blocking such associations can provide a new basis for treating pain.

The meaning of a memory

The way we remember pain depends on the emotional context of the painful event. One study shows that women going through childbirth and gynecological surgery both report high levels of pain. But months later, the women who gave childbirth “forgot” to some extent how much pain they felt, while the women who had surgery overestimated their self-reported pain levels. Apparently the emotional context of pain and its meaning matters for how it is remembered.

A recent article in the New York Times discusses some similar research with marathon runners – they underestimate self-reported pain levels at the finish line if they were also feeling good about the race.

I have a wise neighbor who noticed something similar with his kids after a trip to Disney Land - they didn't seem to enjoy it much - they whined all day about long lines and short rides. But as soon as they got home, they begged to go back at 9am the next day. He called it Disney Amnesia.

I think he had an intuitive understanding of a cool effect studied by Daniel Kahneman (author of the incredible Thinking, Fast and Slow). The peak-end rule states that when someone tries to recollect how much they hated or enjoyed a particular experience, they put too much emphasis on how they felt at the end of it. (They also excessively weight the peak intensity of the experience, and almost totally disregard duration.) This is why people (especially my wife) have a hard time remembering just how boring a vacation was. Or how much pain they suffered in a colonoscopy.

This is all very interesting, but I must admit there may be major differences between “memories of pain”, which are consciously accessible, and “pain memories”, which are more like sustained sensitivities to threatening stimuli. But there are similarities - in each case, the way we feel in regard to past experience depends on idiosyncratic and imperfect processes involving interpretation and emotional context.

I think one way that therapists can help clients with chronic pain is giving them a new way to frame past experiences of injury, and better ways to respond in an emotional intelligent way to new injuries.

How do we get annoying jingles out of our head? Listen to something different. How do we forget how much our back hurt the last time it "went out"? Create as many new memories of pain-free bending as possible.

And how do we prevent new injuries from turning into chronic pain? Experiences are more likely to become indelible memories when accompanied by extreme emotion and stress. Personally, I lead a pretty sporty life, so new aches, pains or injuries are always showing up. Each time, there is a part of me that gets emotional and stressed: "Oh no, this is the end of my soccer career!"

But there is another part of me that knows I might be in a narrow window of time where my emotional reactions to this new pain can play a role in how long it will last. So I try to relax, be mindful, chill out, and talk myself down from any thoughts of catastrophe. I also give my body a chance to engage in whatever instinctive protective movements or postures it wants.

I think I've avoided a lot of potential problems with this mindset. But I'm not really sure how many, because I can't remember most of them.